- Home

- Andy Remic

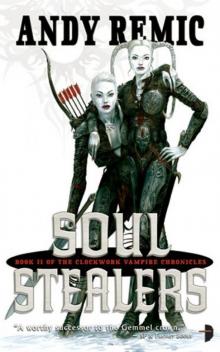

Soul Stealers Page 9

Soul Stealers Read online

Page 9

"What is he then? A camel?"

Kell frowned at Saark, and motioned for the tall swordsman to sit. In a low voice, a tired voice, Kell said, "I told you what I saw. If you don't believe me, then to Dake's Balls with you! You get out there in the snow and look for the little bastard. Me, I'd rather put my axe through his skull. He gives me the creeps."

"You are incorrigible!"

"Me?" snapped Kell, fury rising. "I reckon we brought something bad out of Old Skulkra; invited it out into the world with us. I fear we may have done the world a disservice. You understand?"

"He saved us," sulked Saark, ducking into the makeshift shelter and resting his back against cold, damp rock. He shivered, despite his fur and leather cloak. "You are an ungrateful old goat, Kell. You know that?"

"Saved us?" Kell laughed, and his eyes were bleak. "Sometimes, my friend, I think it is better to be dead."

They shared out some dried beef and a few oatcakes, and ate in silence, listening to a distant, mournful wind, and the muffled silence brought about by heavy, snowladen woodland. Occasionally, there was a crump as gathered snow fell from high branches. At one point, Kell winced, and took several deep breaths.

"You are injured?" Saark looked suddenly concerned.

"It is nothing."

"Don't be ridiculous! You are like a bull, you only complain when something hurts you bad. What is it?"

"Pain. Inside. Inside my very veins."

Saark nodded, his eyes serious. "You think it's the poison?"

"Yes," said Kell, through gritted teeth. "And I know it's going to get worse. My biggest fear is finding Myriam, and the antidote, and not having the strength to break her fucking neck!"

"Do you think Nienna is suffering?"

"If she is, there will be murder," said Kell, darkly, fury glittering in his eyes. "Now get some sleep, Saark. You look weaker than a suckling doe. You sure you don't want some more food?"

"After seeing the result of that albino's corpse ripped

asunder? No, my constitution is delicate at the best of times. After that spectacle, I have lost appetite enough to last me a decade."

Kell grunted, and shrugged. "Food is food," he said, as if that explained everything.

Saark slept. More snow fell in the small hours. Kell sat on the rock, back stiff, all weariness evaporating with the pain brought by poison oozing through his veins and internal organs. It felt as if his body, knowing it was shortly to die, wanted him to experience every sensation, every second of life, every nuance of pain before forcing him to lie down and exhale his last clattering breath.

The dawn broke wearily, like a tired, pastel watercolour on canvas. Clouds bunched in the sky like fists, and the wind had increased, howling and moaning through woods and between nearby rocks which seemed to litter this part of the world. On the wind, they could smell fire. It was not a comforting stench. It was the aroma of war.

Kell, chin on his fist, eyes alert, Ilanna by his side, jumped a little when Saark touched his shoulder.

"Have you been awake all night, Old Horse?"

"Aye, lad. I couldn't sleep. Too much on my mind."

"We will find Nienna," said Saark.

"I don't doubt that. It's finding her alive that concerns me."

"Shall I cook us breakfast?"

"Make a small fire," said Kell, softly. "Hot tea is what I need if these aged bones are to survive much more rough life in the wilderness."

"Ha, it's a fine ale I crave!" laughed Saark, pulling out his tinderbox.

"I find whiskey a much more palatable experience," muttered Kell, darkly.

They drank a little hot tea with sugar, and ate more dried beef. Kell's pain had receded, much to the big man's relief, and Saark was also looking much better after a good sleep and some food and hot tea. They huddled around the small fire, then stamped it out and packed away their makeshift camp. They were just packing saddlebags when Kell hissed, dropping to a crouch and lifting Ilanna before him. Her blades glittered, and in that crouch Saark saw a flicker of insanity made flesh.

Skanda walked from the trees, smiling with his black teeth. He stopped, and tilted his head. On his hand rode the tiny scorpion with twin tails. It seemed agitated, moving quickly about the boy's hand and never halting. Its tails flickered, fast, like ebony lightning.

"I found you," he said. He tilted his head. Kell rose out of his crouch, cursed, and continued to pack the saddlebags, turning his back on the boy with deliberate ignorance.

"Are you hurt?" said Saark, rushing over.

"No," smiled Skanda, "but I led those soldiers on a merry chase. I was not surprised to find you gone when I returned to the old armoury." His eyes shone. "I think I upset Kell, did I not? The great Legend himself."

Kell turned, and smiled easily, although his eyes were hooded. "No lad, you didn't upset me. But I didn't worry about leaving you behind, before you get any noble ideas about friendship and loyalty."

"Have I offended you? If so, I apologise."

Kell placed his hands on his hips. "In fact, boy, you have. You have a rare talent, don't you? The ability to kill."

Skanda stared at Kell for a long time. Eventually, he said, "It is a talent bestowed on the Ankarok. I can kill, yes. I can kill with ease. My small size and odd looks do nothing to highlight the bubbling ancient rage within."

Kell stared into the boy's eyes.

A darkness fell on his soul, like ash from the funeral pyres of a thousand children.

It is not human, he told himself.

It is consummately evil.

I should kill it. I should kill it now…

His hands grasped the haft of Ilanna, his bloodbond axe, and he took a step forward but a shrill note pierced the inside of his skull, and he realised Ilanna was screaming at him, warning him, and the note fell and her words came, and her voice was cool, a drifting metallic sigh, the voice of bees in the hive, the song of ants in the nest…

Wait, she said. You must not.

Why not? he growled.

Because he is of Ankarok. The Ancient Race. They were here before the vachine, and before the vampires before them; they invented blood-oil, and mastered the magick, and they know too much.

Kell snorted. He felt like a pawn in another man's game. I am being manipulated, he thought. But is my sweet blood-drenched Ilanna telling the truth? Or is she lying through her blackened back teeth because she wants something of her own…

This was Ilanna, the bloodbond axe, and she was in control, or so she liked to think. Blessed in blood-oil, and instrumental, or so Kell believed, in the Days of Blood, she offered him a tenuous link with madness, a risk which Kell readily accepted because… well, because without Ilanna he would be a dead man. And if Kell was a dead man, then his granddaughter Nienna was a dead girl.

He should die.

Why? Because you say so?

Kell breathed in the perfume of the axe. The aroma of death. The corpse–breath of Ilanna. It was heady, like the finest narcotic, like a honey-plumped dram of whiskey; and Kell felt himself float for a moment, lost in her, lost in Ilanna… I am Ilanna, she sang, music in his heart, drug in his veins, I am the honey in your soul, the butter on your bread, the sugar in your apple. I make you whole, Kell. I bring out the best in you, I bring out the warrior in you. And yes I ask you to kill but can you not see the irony? Can you not see what I desire? I am asking you not to kill; I am asking you to spare the boy. He is special. Very special. You will see, and one day you will thank me for these words of wisdom. Skanda is Ankarok, he is older than worlds, look into his insect eyes and see the truth, Kell, understand the importance of what I am saying for we will never have another opportunity like this… he will help you find Nienna… help you save those you love.

You bitch.

I am stating the truth. And you know it. So grow up, and wise up, and let's get moving and get this thing done; Lilliath is leading the albino soldiers through the woods. They are coming, Kell, you must make haste…

&n

bsp; Kell opened his eyes. He realised both Saark and Skanda were staring at him; staring at him hard.

"Are you well?" asked Saark, voice soft.

"Aye, I'm fine."

"We can stay a while longer, if you need rest," said Saark, suddenly remembering his own sleep with a sense of guilt. He had allowed Kell to sit up all night; it had been selfish in the extreme.

"No. The soldiers are coming. We should move."

Skanda's eyes went bright. "You want me to go back into the woods? Find them? Kill them?"

"No." Kell shook his head, eyeing the scorpion perched on the boy's hand. Seeing the look, and misreading its meaning, Skanda hid the tiny insect within folds of rough clothing, and Kell made a mental note to check his boots in the morn. "We're heading north. At speed. We're going to find Nienna. We're going to rescue her… or die in the process!"

Myriam crouched beside the still pool, its circumference edged with plates of ice, their layers infinite, their borders a billion shards of splintered and angular crystal. Beautiful, she thought, breathing softly, pacing herself, and then her gaze flickered up, above the ice, to her own reflection and her teeth clacked shut and the muscles along her jaw stood out in ridges as she clenched her teeth tight. But here, she thought, here, the beauty dies.

She had short black hair, where once she had worn it long. Once, it had been a luscious pelt that made men fall over themselves to stroke and touch. Now, she cropped it short for fear the rough texture and dull hue would scream at people exactly what she was: dying.

Myriam was dying, and she still found it difficult to admit, to say out loud, but at least now she had in some way acknowledged it to herself. For a year she had harboured denial, even as she watched her own flesh melt from her bones, and she'd continually conned herself, thinking that if she ate better, exercised more, found the right medicines, then this illness, this fever would pass and she would be well again. However, for the past three years now she had grown steadily weaker, flesh falling from her bones as pain built and wracked her ever slimming frame. She had often joked how the rich fat bulging bitches in Kallagria would pay a fortune to have what she had; now, Myriam joked no more. It was as if humour had been wrenched from her with a barbed spear, leaving a gaping trail of damaged flesh in its wake.

Myriam had travelled Falanor, attempting to find a cure for her sickness. She eventually tracked down the best physicians in Vor, and spent a small fortune in gold, stolen gold, admittedly, on their advice, their medications, their odd treatments. None had worked. What she had gained from her vast expenditure had been knowledge.

She had two tumours, growing inside her, each the size of a fist. They were like parasites, but whereas some parasites were symbiotic – would keep the host alive so that they, also, could live, these tumours were ignorant, killing the host which supported them. Her one small triumph would be they would also die. Yes. But only when Myriam died.

Myriam stared into her reflection, the stretched skin, the gaunt flesh, drawn back over her skull and making her shudder even to look at herself. Once, men and women had flocked to her. Now, they couldn't stand to be in the same room, as if they feared catching some terrible plague.

I am a creature of pity, she realised sadly. Then anger shot through her. Well, I don't want their fucking pity! I just want my fucking life back! I have only existed on this stinking ball of pain for twenty-nine winters. Twentynine! Is that any age to die? Are the gods laughing at me, mocking me with their sick sense of humour? How fair is that, that others, evil men and women, or useless, stupid, brainless men and women, how is it they get to live – and I do not? Who made that choice for me? Which rancid insane deity thought it would be fun?

Tears coursed her gaunt cheeks, and Myriam bit back the need to scream her anguish and pain and frustration through the frozen trees. No. She breathed deep. And she did what she always did. She thought about this day. And she thought about the next day. And she knew she had to take one day at a time, step after step after step until… until she reached Silva Valley. There, she knew, they had the technology to cure her. Using clockwork, and blood-oil, and dark vampire magick.

However, persuading them? That would be a different matter.

Fear flashed through her, then, and she licked dry lips. Her mouth tasted bad. Tasted like cancer. She grimaced, and her belly cramped in pain and she brought herself back to the present with a jolt; they had not eaten for two days. And the sparse woodland in the low foothills leading to the great feet of the Black Pike Mountains contained little game. She would have to work hard if she wanted supper.

Myriam was a skilled hunter. Before her affliction, she had won the Golden Bow three times in a row at the Vor Summer Festival. Now, the cancer ate her, and had sapped her strength, made her aim less true. But she was still a devastating archer, nonetheless.

Myriam crept through the woods, her boots treading softly on hard soil and patches of snow. She picked every footfall with care and stopped often, looking around with slow, fluid movements, her ears twitching, listening, her mind falling in tune with the winter trees.

There!

She saw the doe, a young one, rooting for food. Were there any parents close by? The last thing Myriam needed was a battle with an enraged stag; if nothing else, it made the meat damn tough.

She saw nothing, and eased herself to her knees, allowing her breathing to normalise, to regulate, as she notched the arrow to the bowstring and with a slow slow slow measured ease, drew back the string, taking the tension with her ever-so-slightly trembling muscles.

The arrow flashed through the woodland, striking the doe from behind, between the shoulder blades, and punching down into lungs and heart. It was a clean kill, instant, and the doe dropped. Myriam felt a burst of joy, of pride at her skill; then she stood, and the smile fell from her face like melting ice under sunshine.

Death. She shivered. Death.

Myriam crossed the forest floor and drew a long knife; expertly she sliced the best cuts of meat and placed them in a sack, blood oozing between her fingers. Then she stood, looked around, eyes narrowing. Something felt wrong, but she couldn't place her finger on it; however, Myriam trusted her senses, they were fine honed and reliable. If the element which felt out of key wasn't here, it must be back at camp. Her jaw tightened.

Myriam moved like a ghost through the trees. The world was silent, filled with snow and ice, and occasionally snow clumped from trees with a tumbling rhythm.

She approached the makeshift camp, trees thinning where huge fists of rock punched upwards at the sky, dominating her vision. Myriam felt her throat dry for a moment, for the Black Pike Mountains were a panorama indeed, a line of domineering peaks that lined her sight from the edge of the world to the edge of the world. Each peak she could see reared black and unforgiving into the sky, many damn near ten thousand feet. And beyond, she knew, they got much bigger, much more terrifying, and much more savage.

Myriam stopped, head tilting. The camp was quiet. Too quiet. Her eyes scanned right, where they could see the narrow trail which led from the Great North Road to the gawping maw of the Cailleach Pass; it was along this, she knew, Kell would finally come, head hung low, poison eating him, begging her for the antidote, for her to relieve his pain, for her to slit his throat and end his torment. Only Kell would not; he would be thinking of Nienna, and her suffering, and how he could save her instead.

A cold wind blew, and Myriam shivered. Snow fell from the trees behind her, making her jump, and she realised she had dropped the sack of meat and had notched an arrow to her bow without even realising it. Kell, the wind seemed to whisper. Kell. He will gut you like a fish. He will cut out your liver. He will drink your blood, bitch!

Scowling, Myriam grabbed the sack and stalked into their small camp, where the men, Styx and Jex, had built an arched screen of timber and evergreen fronds, for protection against the wind. Within this semi-circle they'd dragged logs for seats, and built a fire in a square of rocks. The fire burned low. Again,

Myriam's eyes narrowed. To let the fire go out was foolish indeed; here, in this place, it meant the difference between life and death.

"Styx?" she said, voice little more than a murmur. Then louder. "Styx? Jex? Where are you?"

The camp was deserted. Myriam's eyes looked to where Nienna, their young prisoner, had been seated; there were deep marks in the snow created by her boots. A struggle?

"Damn it."

Myriam left the sack at camp, and followed tracks through the woods, kneeling once to examine a confusion of marks. She cursed; they had been using the camp for nearly a week now, and there were too many contradicting signs. Something rattled nearby. Myriam's head came up. She broke into a run, arrow notched, and skidded to a halt before a series of huge trees swathed in ivy, creating an ivy wall on two sides like a corridor; against this backdrop Nienna struggled, and even as Myriam watched Styx, squat, black-lipped Styx, with pockmarked skin and his left eye, uncovered, nothing more than a red, inflamed socket – she watched him push the blade to Nienna's throat and snarl something incomprehensible on a stream of foul spittle down her ear.

Vampire Warlords: The Clockwork Vampire Chronicles, Book 3

Vampire Warlords: The Clockwork Vampire Chronicles, Book 3 The Iron Beast

The Iron Beast Kell's Legend

Kell's Legend Kell’s Legend cvc-1

Kell’s Legend cvc-1 The Dragon Engine

The Dragon Engine Biohell

Biohell Sim

Sim Soul Stealers

Soul Stealers Warhead

Warhead The Iron Wolves

The Iron Wolves Vampire Warlords cwc-3

Vampire Warlords cwc-3 Serial Killers Incorporated

Serial Killers Incorporated Hardcore - 03

Hardcore - 03 Twilight of the Dragons

Twilight of the Dragons A Song for No Man's Land

A Song for No Man's Land Toxicity

Toxicity War Machine (The Combat-K Series)

War Machine (The Combat-K Series) The White Towers

The White Towers Return of Souls

Return of Souls Theme Planet

Theme Planet Cloneworld - 04

Cloneworld - 04 Soul Stealers cvc-2

Soul Stealers cvc-2 Spiral

Spiral Quake

Quake