- Home

- Andy Remic

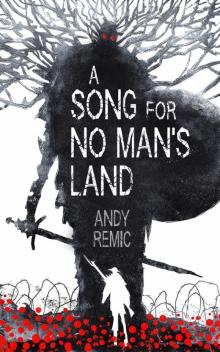

A Song for No Man's Land

A Song for No Man's Land Read online

Begin Reading

Table of Contents

About the Author

Copyright Page

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author's copyright, please notify the publisher at: http://us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

This novella is dedicated to the soldiers who fought in the First World War

Author’s Note

I have replaced the word “fuck” with “——” throughout the text, in the style of early World War I writings where soldiers self-censored; this has been done to help authenticate the text.

Part One

The Somme

The Fighting Cocks Public House.

King’s Cross, London.

3rd. January, 1914.

HE LAY ON HIS back, mind reeling as bloodshot eyes focussed on stars flitting across the high, smoke-stained beams. Remnants of whisky tasted sour, a dead rat on his tongue, and he could hear the muffled public house sounds as if swimming under water, diving deep into a realm of bitter dreams.

The punch knocked Jones clean off his stool, splitting his lip and bruising his jaw; but as he lay, all eyes upon him, and a cold silence descended through the smoke like falling ash, he grinned—because he no longer cared. He had reached the nadir. He’d lost so much money, and they would be coming for him real soon, with balled fists and blazing eyes and harsh words, with bricks and helves, and the pain would follow . . . He’d follow sour whisky down a long tunnel into oblivion darkness. Just like the old days. Back in Wales. In the woods. Hunted by the Skogsgrå.

Damn and bloody hell!

But now, ha yes, now! He would enjoy the drink whilst he could, savour the hot sweet liquor . . . and if his strength didn’t fail him—as so often it did—find a willing woman for the night.

“Come on; up, lad.” A large, bearded man helped Jones to his feet, and the young gambler stood, swaying and rubbing his injured jaw. He hiccupped, then staggered to the bar.

“Another whisky, bartender!”

“Get that ——er out of ’ere!” growled the stocky Cockney landlord.

A tall American with angry eyes and clenched fists moved towards Jones, but the bearded man held up a fist, and in silence, the American subsided, finished his beer, and left the pub. Two minutes later, the gambler was out in the rain, supported by the bearded man, whose face was a scowl.

“Where you staying, lad?”

The reply was a mumble of unrecognisable words. Then Jones’s face suddenly brightened and he managed, “I need a drink. More whisky! Hey . . . where are we going?” He paused, feet kicking the cobbles as he was half-helped, half-dragged along. “Where am I? Who are you?”

The man smiled. “I’m Charlie Bainbridge. Charlie to my friends. Nice to meet you. You were about to get a royal kicking in there, son, and I can’t stand seeing a drunk man battered for no reason. Especially by an American.”

“It . . . would have been all right, Charlie.” Jones waved a hand, as if swatting away a wasp.

“That’s as may be. But you sure can’t be having any more whisky down your throat, or you’ll be decorating the pavement with your supper! Anyway, come on, lad, what’s your name?”

The gambler thought for a while. “I’m Robert Jones. And I ain’t had my supper,” he mumbled, coughing and wiping his nose on his sleeve.

Bainbridge nodded, and continued to drag Jones along the cobbles, and finally dumped him on a scrubbed stone doorstep at the end of a terraced street. Jones reclined, eyes shut, mouth open, the stink of whisky strong on his breath.

“You’ve had a skinful, all right, lad,” said Bainbridge, tugging a cigarette from his pocket, cupping it to his mouth, and lighting it with a flare that illuminated his dark, brooding eyes in thick eye sockets. “Maybe you should curl up and go to sleep right there? Damned if I can carry you all the way home.”

Suddenly, there came a clattering of boots at the end of the street. A harsh voice bellowed, “You there!” and echoes bounced from house to house as long shadows stretched ahead.

Bainbridge blew smoke from his nose and picked a bit of tobacco from the tip of his tongue with thick fingers. He watched as three large-set men pounded down the street, hobnailed boots heavy and scuffed, clothes rough and unwashed.

“You all right, gents?” asked Bainbridge, turning and placing himself between the half-conscious, grinning, oblivious figure of Jones, and the three men who slowed their run and stopped under the glow of a streetlamp.

“He owes Tyson a lot of money,” said one man, who had a thick bull neck and shaved head. His eyes were small, like a pig’s, and looked past Bainbridge to the slumbering gambler. “We’ve come to claim what is owed.”

“Oh, yes?” said Bainbridge, drawing deeply on his cigarette. “Well, lads, I think he’s in no position to pay just this minute. You can see that. Now, you come back in the morning, and he’ll sort you out, I’m sure.”

“You’d be Charlie Bainbridge, eh?” said the cocky newcomer with the bull neck, turning his head and fixing his piglet gaze on Bainbridge proper.

Bainbridge nodded, watching the leader of the three roll up his sleeves and crack his knuckles with a smile. “I have heard a lot about Charlie Bainbridge . . . I’ve heard you’re quite a man with your fists?”

Bainbridge sighed, flicked away his cigarette, rolled back on his right hip and delivered a powerful hook to the jaw that sent a tooth skittering across the cobbles like a rolled die, and saw bull-neck twitching on the ground, piss staining his unwashed trousers. The other two men rushed in and shadows danced against the wall as Jones, who had been watching the glowing tip of Bainbridge’s discarded cigarette, closed his eyes and began to snore.

The French Offensive:

Battle of Flers-Courcelette.

16th. September 1916.

DISTANT MACHINE GUNS roared, like some great alien creature in agony. Rain lashed from unhealthy iron skies, caressed the upturned faces of soldiers praying to a god they no longer believed in for a miracle that couldn’t happen.

A sudden explosion of mortar shell and the Tommies flinched—some half-ducking, fear etched clear on frightened young faces. Debris rained down behind the trench and the men let out deep sighs, turned pale faces to the sky once more, and gripped the slippery stocks of rifles in a desperate prayer of reassurance.

Explosions echoed, distant, muffled. The ground trembled like a virgin. Occasionally, there was a scream from out there, and whistles pierced the Stygian gloom from other parts of the trench as battalions headed out into the rain and the treacherous mud.

Tommies exchanged half-hearted jokes and anecdotes, laughed over-loud, and slapped one another on the back as guns roared and crumps shattered any illusion of safety.

Deep in the trench, two men stood slightly apart, talking quietly, refusing to be drawn into any false charade of happiness; one was a large man, his close-cropped hair stuck at irregular angles, his face ruddy with the glow of adrenalin and rising excitement, his knuckles white as they gripped the stock of his rifle. The other man was smaller in stature, his face pale, hair lank with falling rain and sticking to his forehead. They were waiting, waiting patiently. Out there, it seemed the whole world was waiting.

“I ——ing hate this,” muttered Bainbridge after a period of silence, baring his

teeth. “It’s all arsapeek. I want to be over the top. I want to do it now!”

“It’ll come soon enough,” soothed Jones, brushing hair back from his forehead and rubbing his eyes with an oil-blackened hand. “When the brass hats sort their shit out.”

“It’s the waiting that’s the worst. An eternity of waiting!”

Jones hoisted his SMLE, and at last the captain appeared, a drifting olive ghost from the false dusk. The whistle was loud, shrill, an unmistakable brittle signal, and the sergeant was there offering words of encouragement, his familiar voice steady, his bravery and solidity a rain-slick rock to which the limpets could cling.

The Tommies pulled on battered helmets, then Bainbridge led Jones towards the muddy ladders, and the men of the battalion climbed—some in silence, some still joking, most feeling the apprehension and a rising glow of almost painful wonder in their chests, in their hearts. Most of the men were new conscripts, a few were veterans; all felt the invasive and terrible fear of the moment.

Hands and boots slipped on muddy, wet rungs.

Overhead, shells screamed, cutting the sky in half as if it were the end of the world.

And then they were over the bags.

Diary of Robert Jones.

3rd. Battalion Royal Welsh Fusiliers.

16th. September 1916.

I’m off the whisky now, and this is making me push on, making me strive for a new beginning. I can’t help feeling this is a mistake, though; I am out of place in a smart uniform, taking orders from the brass. And my haircut is ridiculous. No women for Rob Jones now!

I’ve learnt much from Bainbridge in this hole. He’s taught me with his fist to lay off the whisky, as that’s the reason I’m here. Him—he enjoys the fighting, I think. Another challenge for the warrior inside him. He’s a born soldier.

I went into battle today, over the bags with the rest of the company and tasting fear and wishing like hell for just a sip of that warm heaven. It is strange, the things a man remembers when under pressure, pinned under gunfire, when suffering fear and disgust at a situation into which he is forced. I remember my wet boots, the bastards, soaked with mud and water because the trench had flooded. God, that stunk.

I remember the chats, lice in my hair, wriggling, and cursing myself for not getting to the delouse.

I remember the rough texture of the wooden rungs on the ladder as I climbed to go over the bags, each rung a cheese grater, shredding my skin, dragging at my boots as if warning me not to go over the top.

It all seemed like a dream. Surreal.

The ground was churned mud, harsh, difficult to cross; the noise was like nothing I’d ever experienced before! The crack of rifles, the ping and whistle of bullets, the roar of machine guns from the Hun trench. My friends went down screaming in the mud, hands clawing at the ground; some were punched back screaming to the trench, their faces and chests torn open, showing ragged strips of meat, smashed-in skulls. Some vomited blood to the earth right there before me. And there was nothing I could do to help them, the poor bastards.

I pounded on beside Bainbridge, muscles hurting, mouth dry, and Bainbridge was shouting, shouting, always bloody shouting like a maniac! We ran past trees, stark, arthritic ghosts in the gloom, shot to hell and stinking a sulphur stink, a sad contrast to the bright woodlands of my youth in glorious Wales . . .

There were tanks—great, lumbering terrifying machines belching fumes and grinding through mud; we loved the tanks, though, because we used them for cover, ducked our heads behind their metal husks, breathed their stinking fumes, their unholy pollution as bullets rattled from iron hulls. I remember thinking how frightening they were, but not as frightening as the smash of crumps tearing holes in the ground; not as frightening as the continuous roar of those ——ing machine guns. The guns never seemed to stop, and I remember thinking each tiny click of that perpetual noise was a bullet leaving the chamber, a bullet that could smash away life, delivering death in a short, sharp, painful punch.

We—a few men from my battalion—reached an old barn or some similar kind of building; it surprised us, rearing suddenly out of the smoke-filled gloom, and we waited there to catch our breaths. I noticed nobody was telling jokes now. Nobody was ——ing smiling. I took the time to look in the men’s faces, tried to imprint the images in my skull in case they were killed. I would have liked to remember them, remember them all—but out there, it was a sad dream.

I was despondent, feeling the whole world had forgotten us in that insane place of guns and mud and noise. The girls back home could never understand. How could they? All they saw were pictures of smart Tommies in their uniforms marching off to battle. The proud British Tommy! It made me want to puke.

We were forgotten, left there to fight an insane battle and die for something we did not understand, that no longer mattered. It was a terrifying thought and my head was spinning.

Most of all, I remember the fear. Like black oil smothering me.

And so I tried to escape, into dreams of childhood.

Back, to Dolwyddelan, and the wonderful woods near Gwydyr Forest where I played as a child, under the watchful, stern gaze of Yr Wyddfa, my sentinel.

Even back then, I never managed to grasp the truth, or the reality . . . But then, that was a million years ago.

At Flers-Courcelette, I would have sang to the Devil for a drink, and Bainbridge was good to me. He supported me, gave me help, urged me on when I thought I could go no further. Bainbridge was a true friend, and I thank him here in my diary—I thank him for keeping me off the whisky, and for keeping me alive.

Thank you, Charlie.

Flers-Courcelette.

The Field, 28th. September, 1916.

“COME ON, LAD,” growled Bainbridge, placing his hand on Jones’s shoulder. “Our brothers are fighting out there, getting outed, and we’re crouched here like we’re having a shit in a possie.”

Jones nodded, took a long, deep breath, and looked around; most of the battalion had moved out again, and some of the tanks had foundered, sitting in the mud like stranded monsters, lurking in the mist, waiting for unsuspecting soldiers to creep past. Some revved engines, grinding, others were silent, squatting at fallen angles in shell holes, like broken siege engines.

Jones took hold of his rifle, spat, “Let’s move, then,” and followed Bainbridge out into the world of mud and smashed trees. They crept past a low wall of chewed stone, over corpses of fallen men like twisted dolls, and Jones kicked a length of barbed wire out of his path.

They were close to the enemy line now, could see the blackened smear across the earth like some great dark wound. Machine guns roared in bursts, and rifles cracked. The objective was simple—take the enemy communications trench. A simple order filled with clarity. Easy for the bastards to type on a clean white page back at HQ. But in the real world, out here, not quite such an easy task . . .

Bainbridge felt good. The fear and frustration of waiting had gone. The rush of the advance was with him, in his heart, in his mind—his rifle an extension of his person, a finely tuned tool of death at his fingertips. Somebody would pay for all that waiting, all that fear, all the lice. Somebody would pay for all the corpses. The bodies of dead friends, lost comrades. Somebody would pay in blood.

Jones felt a cold, creeping terror. His guts were churning. Every time he stepped over a corpse, the face like an anguished ghost, silently screaming, he felt himself die just a little bit more inside. There was no respect out here. No dignity.

“Bainbridge, slow down,” he hissed, slipping in mud. He glanced left, could see other Tommies moving through the gloom of mist and gun smoke. There was a burst of machine gun fire, and he saw three men go down, arms flailing like rag dolls.

Bainbridge hit the ground on his belly. “Bastards.” He gestured, and Jones slid up beside him.

They were close now. Could see the sandbags and barbed wire of the Hun trench.

“You ready, lad?”

Jones gave a silent nod.

Panting, Jones pried away the fingers and grimaced at their warm, sticky touch. He looked around, suddenly disengaged from his private battle. Bainbridge and another Tommy were charging away, two enemy Hun fleeing. To the right, the trench was empty. They were there. In the communications trench.

Jones moved slowly after Bainbridge, heart pounding, and rubbed dirt from his stinging eyes. He lifted his SMLE, seeing the bayonet with its indelible stain. The boards rocked beneath his boots. His mouth was drier than any desert storm.

Vampire Warlords: The Clockwork Vampire Chronicles, Book 3

Vampire Warlords: The Clockwork Vampire Chronicles, Book 3 The Iron Beast

The Iron Beast Kell's Legend

Kell's Legend Kell’s Legend cvc-1

Kell’s Legend cvc-1 The Dragon Engine

The Dragon Engine Biohell

Biohell Sim

Sim Soul Stealers

Soul Stealers Warhead

Warhead The Iron Wolves

The Iron Wolves Vampire Warlords cwc-3

Vampire Warlords cwc-3 Serial Killers Incorporated

Serial Killers Incorporated Hardcore - 03

Hardcore - 03 Twilight of the Dragons

Twilight of the Dragons A Song for No Man's Land

A Song for No Man's Land Toxicity

Toxicity War Machine (The Combat-K Series)

War Machine (The Combat-K Series) The White Towers

The White Towers Return of Souls

Return of Souls Theme Planet

Theme Planet Cloneworld - 04

Cloneworld - 04 Soul Stealers cvc-2

Soul Stealers cvc-2 Spiral

Spiral Quake

Quake