- Home

- Andy Remic

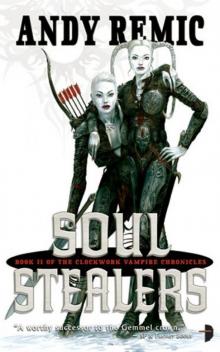

Soul Stealers Page 7

Soul Stealers Read online

Page 7

Jekkron, tall, elegant, a warrior born, loomed over Kell who was groaning, eyelids fluttering. The old soldier had lost his axe amidst bricks and snapped timber joists. He opened his dust-smarting eyes and snarled through bloodied teeth but the albino smiled, and gave a single nod of understanding; his black sword lifted high, then hacked down at Kell's throat.

CHAPTER 3

Clockwork Engine

"So, he has betrayed us?"

Silence echoed around the Vachine High Engineer Council. The two Watchmakers present squirmed uneasily, for this entire concept was anathema to everything in which they believed, and aspired. "That's impossible."

"Why impossible? A canker, by definition, should be impossible. We are the Higher Race, the Blessed; we are at the pinnacle of flesh and technological evolution. What then is a canker? A mockery of our genetics, a mockery of our humanity, a mockery of our vachine status. The vachine should be perfect; the cankers remind us we are not. How, then, can it be construed that Graal's betrayal is an impossibility?"

Another voice. Old. Revered. Serious. "He has served us for a thousand years. You… young vachine do not understand what General Graal has done for us. Without him, and without the work of Kradek-ka, we would never have achieved such an exalted state; we would never have reached our current evolutionary curve, plane, and High Altar. Graal accelerated our species.

Without him our race would be dead."

Silence met this statement. Great minds contemplated the implications of their discussion.

A voice spoke. It was young, nervous, a chattering of sparrows next to the wisdom of the owl. "The clock work is all wrong," said the voice.

"Meaning?"

"The algorithms… they tell of the Axeman."

"What is this Axeman?"

"The Black Axeman of Drennach."

Again, another pause. Around the table, some of the elder vachine lit pipes and puffed on smoke laced with the heady narcotic, blood-oil. A silence descended. Several elder vachine exchanged glances.

"The clockwork engines are never specific, but they speak of a terrible killer, an axeman named Kell – but is he friend or foe? The machines will not say. They just bring up his name again, and again, and again." "We must assume he is the enemy. Every other human to set foot in Silva Valley has had nothing but evil and destruction in their corrupt and festering hearts." "Is that not to be expected?" "Meaning?"

"We feed on them; they are like cattle to us."

"Still, we must assume this Black Axeman is evil, a scourge to our kind. But then, we are straying from the real problem here; that of General Graal, and what he is doing with our Army of Iron." Silence greeted this.

"Has the report come back, yet? From Princess Jaranis?" "There has been no communication; nothing."

This was considered. Digested. And then one of the Watchmakers stood; in the structure of the vachine religion, only the Patriarch ruled over the Watchmakers, and the Watchmakers were few enough now to make their rank a dying breed – only five of them left. General Graal was Watchmaker; this was the element of their new information which made the High Council so nervous. Nobody wished to sound like a Heretic; nobody wished their clockwork poisoned, their flesh to be torn and twisted forcibly into canker.

She was called Sa, small of stature, but with flashing, dangerous eyes. To cross Sa was to be exterminated. "We have little evidence," she said, voice smooth, eyes fixing on every member of the Engineer Council in turn. She walked around the outside of the huge oval steel table, and stopped at the head where once, in good health, the Patriarch would have sat; today, as on many days, he was confined to his bed. It was rumoured he coughed up blood-oil, and his days were numbered. "We cannot simply condemn General Graal in his absence; he should be able to defend himself against the diabolical accusations that have taken place over this table. What is happening here?" Her eyes glowed. "We used to be united. Now, we are crumbling. We will adjourn, and no more will be spoken on this matter until Graal returns in the spring after Snowmelt. Is this agreed?" There came a murmur of agreement, and the Engineer Council disbanded, the hundred or so members flooding out into the warren of the Engineer's Palace, and beyond, to Silva Valley. Finally, only Sa and Tagortel, another esteemed vachine Watchmaker, were left. Their eyes met, like old lovers on a secret tryst. "I don't think it will be enough," said Tagor-tel. "I do not trust the old General. And… isn't that why Jaranis was despatched? To keep an eye on proceedings?"

"The weather is against her." "Convenient. For Graal."

Sa puckered her lips, brooding. "I, also, have noticed changes in Graal. However, I do not see how one man could be a threat to the High Engineer Episcopate. To the Vachine Civilisation! Even with our obedient Army of Iron under his direct control. What would he do? Turn them against us?" She laughed, a sound of spinning flywheels.

Tagor-tel shrugged. "I doubt he would have the persuasion. The alshina have served for too long." He thought for a moment. "We need to discover what happened to Jaranis. She had the Warrior Engineers, did she not? Walgrishnacht? He is one of our ultimate soldiers. If anybody will return word, he will." "We will see. But let us assume, for a moment – away from concepts of heresy – that Princess Jaranis has failed. That she and her entourage are dead. What then?" "We can ask…" Tagor-tel paused, and checked the chamber, making sure they were alone. His voice dropped. "Fiddion." "You think he will cooperate?"

"He has, shall we say, passed us sensitive information before. Graal seems to have some bond with the Harvesters; and the Harvesters play by their own rules. It is worth a try. For whatever reason, Fiddion despises his own kind."

"Do it. Contact Fiddion. Let us see if the Harvesters know what Graal plots."

Sunlight glimmered between towering storm clouds, rays of weak yellow that cast long, eerie shadows over the forests surrounding Old Skulkra. Graal strode through the camp, trailed by three Harvesters, one hand on his sword hilt, his pale-skinned face unreadable. Albino soldiers moved from his path, and he stopped only once, head turning left, as the snarls from the canker cages set his teeth on edge. Damn them, he thought. Damn their perverse twisted flesh! They reminded him, painfully, of his brother. Dead, now. Murdered, so he later discovered, by the bastard Kell and his bloodbond axe. "I'll see you burn, motherfucker," he muttered as he continued through the camp and reached the edge of the tents where albino soldiers still had campfires burning.

Several soldiers looked up at his approach, glances subservient, as if waiting for instruction. Graal did not acknowledge their existence. Instead, his eyes were fixed on the three huge black towers which sat on the plain: angular, cubic, squat, their surfaces matt black, their intentions not immediately fathomable.

"Are we ready?" said Graal.

"We are ready," hissed one of the Harvesters, sibilantly.

"Is he here?"

"He is here, General Graal."

"Good. It is about time."

Graal strode out across the plain, and the closer he moved to the Blood Refineries, the larger they seemed: mammoth cubic structures, the black surface of unmarked walls flat, and dull, like scorched iron. Wisps of snow snapped in the air as Graal strode across frozen earth, and as he came near his nose wrinkled. He blinked. The corpses, four thousand in total, stripped of armour and boots, had been laid out in rows before the three Blood Refineries. Graal glanced down, but no flicker of emotion showed across his pale face. He had more important matters on which to worry.

The Refineries towered, and he walked in their shadow. There was a man, tall and lean and bearded, reclining against the first Refinery. Graal reached him and stopped. This was Viga, Kradek-ka's personal Engineer Assistant, come to oversee the Blood Refineries and their absorption. He had travelled all the way from the Black Pike Mountains to help.

"Well met, Graal," said the man, eyes glittering, and Graal could just distinguish tiny vachine fangs, like polished brass, peeking over his bottom lip.

"I thought you would never come," said Graal,

fighting hard to keep his annoyance in check. He was not used to being treated so… casually. "Was the journey difficult?"

"More difficult than you could comprehend," said Viga, rubbing at his beard. "Although I hear you suffered some disturbance yourself; something to do with an old, bearded soldier? A resident of Jalder, or so I was informed."

Graal forced a smile. "A nothing," he said. The Harvesters were watching him, waiting for his command; as if waving away an insect, he gave instruction, and the Harvesters started to lift the half-frozen corpses and feed them into long, thin slots at the base of the Refineries. It took very little effort: the instant a body touched the slot, it was sucked inside. A deep thrumming seemed to well up beneath the ground, and Graal fancied he could sense, if not necessarily hear, the huge but subtle clockwork engines within the Blood Refineries; mashing up bodies, extracting blood, and refining it into blood-oil: the food of the vachine world.

The bearded man turned, and watched for a while. Then he tutted. Graal stared into his eyes, and the man lowered his head.

"There is a problem?"

"Kradek-ka's daughter."

"She was always a problem."

"Do not be flippant with me, Graal; you know her existence is the reason you stand here now, you know the experimentation Kradek-ka performed on her was the central reason why we can do this; without her, without Anukis and her," he laughed, "her jewel, there would be no quest for Kuradek, Meshwar and Bhu Vanesh."

"You are of course, correct," said Graal, and straightened his back. Beside them, the Harvesters continued to pick up corpses and feed them into the Refineries. Deep inside, now, the meshing of gears could be heard; and huge pendulous blades working.

Graal glanced up, at the towering wall of the Refinery, and then back to Viga. He reached out to place a comforting hand on his arm, but the man recoiled.

"No. You must not touch me. I am impure!"

"We are all impure," said Graal, head tilting a little; he could see, now, that the man before him was a man ready to crack, a vachine teetering along a blade-edge of insanity.

"We should never have treated her like that. It was wrong of us to push her; to humiliate her!"

"It is too late for regret," said Graal, voice steady.

"Not so! She has escaped, gone looking for her father! Nobody should have undergone such humiliation!"

"Well, she will save us the quest," said Graal, voice hard now. This man's weakness was starting to upset him. He had great respect for Viga, especially as Kradekka's most trusted Engineer servant; but to whine thus? To whine was to be weak; and Graal so hated the weak. He placed his hand on sword-hilt.

"This whole situation is an abomination," continued Viga.

Graal drew his sword, and shook his head, and stepped close to the man and the blade touched his throat, cold black steel pressing flesh and his fangs ejected, suddenly, with a hiss of fury but Graal leant on the blade and blood bubbled along the razor edge and he felt Viga relax beside him. "It is too late to back out now," said Graal, voice little more than a whisper.

"I know that. It's just… she was an innocent vachine! We ruined her life!"

"She is in the past…" said Graal. "So be silent, and be still, and be calm; the Refineries must work, and we must build the store of energy… of magick! Only with the Refineries at optimum power can we bring about the return of the Vampire Warlords!"

"But you do not have the Soul Gems," whimpered Viga, from behind Graal's blade.

"I am working on it," growled Graal, and sheathed his weapon.

Viga had gone. Graal sat on the ground, cross-legged, and watched as the last of the bodies was fed into the huge machines. He looked around, as flakes of falling snow whipped back and forth in the wind. The distance was hazy, just like Graal's memory.

In silence, the last of the Falanor corpses were fed into metal holes. Then the Harvesters did a strange thing. They moved, each to their own Blood Refinery, and they spread arms and legs wide and shuffled forward towards blank metal walls – so they were stark contrasts illuminated against wide plates of iron. And then they – merged, sinking into the metal of the Refineries, becoming for a moment at one with the machines as flesh became metal and iron became flesh, and Graal blinked, licking his lips, nervous for just an instant – not nervous of pain or mutilation or death, even his own death, but nervous in case it did not work. Graal blinked, and the Harvesters were gone; absorbed into the machines. Distantly, he could hear a tick, tick, tick, as of huge, pendulous clockwork.

He smiled grimly. They called it Interface. Where the Harvesters used special ancient magick to refine blood, into that chemical agent the vachine craved, and indeed needed, to survive.

Blood-oil. The currency of their Age.

Graal sat, grimly, thinking about Kradek-ka. The vachine was a genius, no doubt; he had helped usher in the civilisation and society they now enjoyed. However, he was unpredictable, and a little insane. And his daughter was another problem entirely. Graal's face locked. She was yet just another problem he would have to face.

General Graal sighed, and sat staring at the exhaust pipes on one of the Refineries; slowly, the pipes oozed trickles of pulped flesh to the snowy ground. Graal brooded, waiting for his Harvesters to return.

If only all life was as simple as war, he thought.

When the Vampire Warlords return, there will be more war. He smiled at that, and dreamed of his childhood… over distant millennia.

They called him Graverobber, and he lived amidst the towering circle of stones at Le'annath Moorkelth… The Passing Place. The name, and nature, of the stones had long since been lost to the humans who inhabited the land, with their curious ways and basic weaponry. But the Graverobber knew; he had researched, and learned, and been privy to a knowledge older than man or vachine.

He sat, squatting at the centre of the stone circle, watching the snow falling around the outskirts. He loved the winter, the cold, the snow, the ice, the death.

He looked down at himself, analysing his body in wonder. This is what he always did. This is what made him what he was. Narcissistic was not something in the Graverobber's lexicon, but had it been there he would have agreed; for the Graverobber loved himself, or rather, he loved what he had become. What had been made of him, by the Hexel Spiders, over a long, long, long period of time… a journey so long, so arduous, so painful, he no longer remembered the beginning. Now, only now, he knew that he was nearing the end.

Jageraw looked down at himself, at his twisted, corrugated body, his skin a shiny, ceramic black like the chitin of the spider, the spider I tell you – can you smell the hemolymph? It flows in my veins and in my blood and he stared down; his limbs thin, painfully thin, so thin you would think they would snap but Jageraw knew they were piledrivers, ten times stronger than human bone and flesh and raw tasty muscle; a hundred times more powerful yes yes. His head, he knew, for he had seen it reflected in puddles of blood, was perfectly round and bald and he had slitted eyes and a face quite feline, like the cats he used to eat, I like those cats, tasty, all mewling and scrabbling with pathetic claws against his ceramic armour until he snapped their little necks and ate them whole, fur, whiskers and all.

Warlords!

He almost screamed, for he had made himself jump.

He had dreamed about them. About the Warlords, the Wild Warlords, the Vampire Warlords, the precursor to the vachine that lived in the mountains; their kindred, from baby to ape and beyond, and he laughed, a crackle of feline spider and something else dropped in there like oil in water; the cry of a child.

And now! The sheer concept made Jageraw shiver. For the Warlords were an enemy to be feared, he could sense it, he could feel it, and Jageraw had played out the dream, the events to come, the promise, the prophecy yes I did in my mind a thousand times; and despite his strength, despite his awesome killing powers, despite his supernatural abilities of skipping and murder; well, he was afraid.

"The King is dead, the King is dead, the Kin

g is dead," he crooned to himself, voice a lullaby, voice music to his own ears, on a different level of aural capability, if not to the pleasure of anybody else. He knew it would happen, for he had seen it would happen, and the mighty had fallen, the great had toppled, and King Leanoric the Battle King was dead and his army erased and fed into the machine, the nasty black machine to make the drug for vachine.

The Graverobber rocked, chitin covered in a fine layer of snow. He heard a laboured breathing, panting, something under the hunt; interesting, he thought, because usually – in these odd scenarios – he got to feed on both hunter and hunted. A double feast. Lots of food for Jageraw. Lots of food including (he winked at himself and I like it, I do like it) those slick warm organs. How he did like a bit of kidney to wash down the old claret; how he did lust after a morsel of shredded lung. Tasty as a pumpkin.

The breathing was louder now, but it was hard for the Graverobber to see through thick tumbling snow; it swirled this way, it swirled that way, it swirled every damn way, but it certainly got in the way. Jageraw hunkered down, muscles bunching, and decided to kill the hunted first. Then turn on the attackers and rip off their heads, no matter how many there were. Three or thirty, it made little difference to the Graverobber; when he was in the mood for killing and feeding, then he would take his time and savour and hunt, until all of them were dead. They left a stink trail worse than any cesspit odour; it was never hard to follow.

Vampire Warlords: The Clockwork Vampire Chronicles, Book 3

Vampire Warlords: The Clockwork Vampire Chronicles, Book 3 The Iron Beast

The Iron Beast Kell's Legend

Kell's Legend Kell’s Legend cvc-1

Kell’s Legend cvc-1 The Dragon Engine

The Dragon Engine Biohell

Biohell Sim

Sim Soul Stealers

Soul Stealers Warhead

Warhead The Iron Wolves

The Iron Wolves Vampire Warlords cwc-3

Vampire Warlords cwc-3 Serial Killers Incorporated

Serial Killers Incorporated Hardcore - 03

Hardcore - 03 Twilight of the Dragons

Twilight of the Dragons A Song for No Man's Land

A Song for No Man's Land Toxicity

Toxicity War Machine (The Combat-K Series)

War Machine (The Combat-K Series) The White Towers

The White Towers Return of Souls

Return of Souls Theme Planet

Theme Planet Cloneworld - 04

Cloneworld - 04 Soul Stealers cvc-2

Soul Stealers cvc-2 Spiral

Spiral Quake

Quake